It’s about 3.16. Why fight COVID-19 when you can instead make a program in Rust to confirm a mathematical fact that’s been known for millenia?

This is part 1 of the ongoing pi_overkill series.

Background

I’ve heard a lot of things about Rust, and how it’s designed to ensure memory and thread safety without sacrificing on performance relative to C++. What also particularly caught my attention is that, as of 2020, for the fifth year in a row, it’s the most loved language by a large margin in the Stack Overflow Developer Survey. Even better, there’s a Rust textbook avilable online at no cost, so I hardly had a reason to avoid trying it out. What better way is there to learn about Rust’s praised features than to make a program that uses them?

My goal was to make a program that iteratively determines that value of pi using an algorithm that’s very easy to parallelize. What algorithm? Well…

Algorithm

On March 14, 2017, mathematics educator Matt Parker celebrated Pi Day by calculating the value of pi by rolling a pair of 120-sided dice a thousand times. He then tracked how many of the pairs were coprime (meaning that 1 is the only number that can evenly divide both numbers). The probability that a pair of random positive integers are corpime turns out to be 6 / pi^2, so rolling a lot of dice and counting the coprimes is definitely a way to approximate that probability!

Side note: the reciprocal,

pi^2 / 6, happens to equal the sum of all reciprocals of squares. This 3Blue1Brown video explores how pi manages to appear in this scenario.

From there, one can isolate the value of pi: pi = sqrt(6 * total_pairs / coprime_pairs).

Introducing pi_overkill

pi_overkill 0.2.2 is my first substantially complete attempt at implementing this algorithm in Rust. However, instead of rolling 1000 pairs of 120-sided dice, pi_overkill is currently hardcoded to generate 48 million pairs of integers (that can be as large as 4 billion) and divide the work among 12 threads.

Each thread has its own pseudorandom number generator that produces a uniform distribution of u32 integers, except for 0 and the biggest possible u32. After finishing its job counting coprime integer pairs, each thread uses message passing to send its results to the main program thread.

pi_overkill in action

Now, let’s see how accurate and fast pi_overkill is at estimating the value of pi. I’m running these trials on an AMD Ryzen 5 2600 at stock settings.

One thread

For the sake of discovery, let’s pretend I’m running the 0.1 version of pi_overkill, which was only single-threaded. I’ll do that by changing the hardcoded iteration values at the start of the main function.

fn main() {

let num_iterations: u32 = 48_000_000;

let num_threads = 1;

I’ll also time it in my terminal to set a performance baseline.

$ cargo build --release

Compiling pi_overkill v0.1.0

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.55s

$ time ./pi_overkill

Thread 0 is starting

π = 3.1414340216137675

Calculated in 48000000 iterations across 1 threads

Percentage error: 0.005049412623381322%

real 0m5.201s

user 0m5.185s

sys 0m0.005s

On just one thread, it took 5.201 seconds of real time to run 48 million iterations of this algorithm. On this specific run, pi_overkill got 3 digits past the decimal correct.

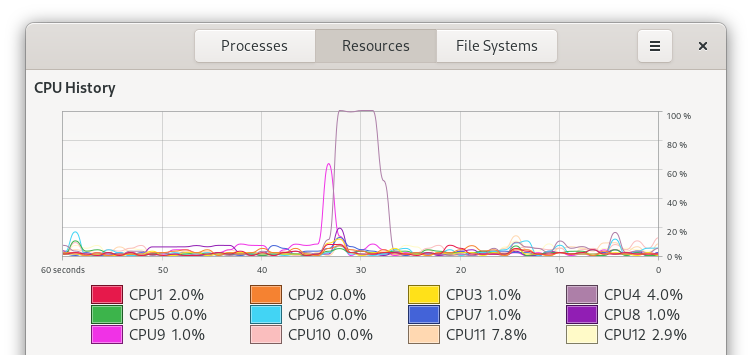

Looking at the system usage, nothing is that surprising, though it seems that there was some indecision early on regarding where in the CPU to run the job.

What if we tried more power?

Six threads

Splitting the 48 million iterations across six threads sounds like it could cut down execution time. I’ll change the program like so:

fn main() {

let num_iterations: u32 = 8_000_000;

let num_threads = 6;

How long does that take?

$ cargo build --release

Compiling pi_overkill v0.1.0

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.51s

$ time ./pi_overkill

Thread 0 is starting

Thread 2 is starting

Thread 3 is starting

Thread 5 is starting

Thread 1 is starting

Thread 4 is starting

π = 3.1415416715219417

Calculated in 48000000 iterations across 6 threads

Percentage error: 0.0016228096215153975%

real 0m0.926s

user 0m5.484s

sys 0m0.004s

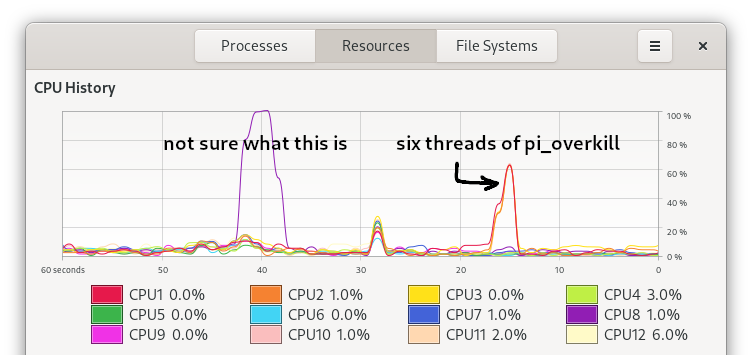

So with six times the threads, the run time is down to roughly a sixth of what it used to be. Also note how the operating system executes the println!s announcing the beginning of every thread in an arbitrary order.

In the CPU usage graph, we can see that the job finishes so quickly that the cores barely pick up. Keep in mind that the line of this graph is smoothed over a time interval.

What if we tried more power?

Twelve threads

Running the 48 million iterations over six threads is pretty cool, but my Ryzen 2600 is a six-core, twelve-thread processor. Having pi_overkill start twelve program threads lines up aesthetically, then. This is the setup that’s hardcoded in pi_overkill 0.2.2.

fn main() {

let num_iterations: u32 = 4_000_000;

let num_threads = 12;

Now let’s run it. If six times the threads reduced execution time to a sixth, maybe two times the threads will halve it.

$ cargo build --release

Compiling pi_overkill v0.1.0 (/home/snowflake/Desktop/pi_overkill)

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.50s

$ time ./pi_overkill

Thread 0 is starting

Thread 1 is starting

Thread 2 is starting

Thread 3 is starting

Thread 4 is starting

Thread 5 is starting

Thread 6 is starting

Thread 9 is starting

Thread 8 is starting

Thread 7 is starting

Thread 10 is starting

Thread 11 is starting

π = 3.141726801416975

Calculated in 48000000 iterations across 12 threads

Percentage error: 0.0042700579601984145%

real 0m0.573s

user 0m6.509s

sys 0m0.011s

That hypothesis was roughly correct! Also note how the sys time is longer than in previous runs, which means that more time was spent in the Linux kernel to execute this program. I don’t actually know why it took longer, but I’m guessing it’s because the kernel had to start more threads.

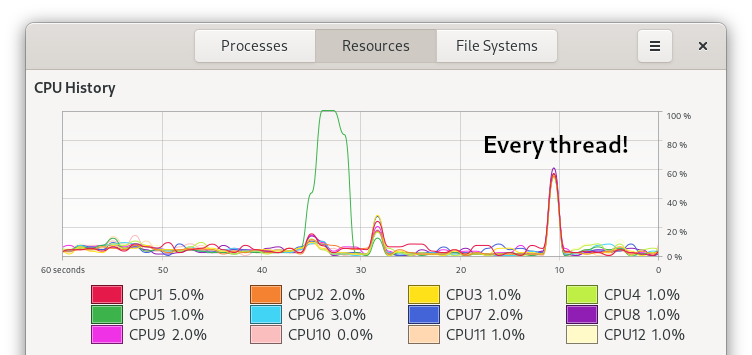

And as expected, all threads of my CPU got to working on this job.

Okay, multithreading in Rust is pretty easy and cool. But what if we tried more power?

Twenty-four threads

The AMD Ryzen 9 3900X has twelve cores and twenty-four threads, but that’s not relevant to my 2600’s six cores and twelve threads. Let’s spawn 24 threads with 2 million iterations each!

$ time ./pi_overkill

Thread 0 is starting

Thread 1 is starting

Thread 2 is starting

Thread 3 is starting

Thread 4 is starting

Thread 6 is starting

Thread 5 is starting

Thread 7 is starting

Thread 8 is starting

Thread 9 is starting

Thread 18 is starting

Thread 21 is starting

Thread 20 is starting

Thread 22 is starting

Thread 23 is starting

Thread 19 is starting

Thread 10 is starting

Thread 13 is starting

Thread 11 is starting

Thread 17 is starting

Thread 16 is starting

Thread 15 is starting

Thread 14 is starting

Thread 12 is starting

π = 3.141381600115296

Calculated in 48000000 iterations across 24 threads

Percentage error: 0.006718040744579934%

real 0m0.587s

user 0m6.435s

sys 0m0.012s

It’s clear that starting more threads than my processor can handle doesn’t have an impact on execution time.

What if we tried way too much power?

192 threads

No processor currently available to consumers can have this many threads at once. Each thread will run 500_000 iterations. This time, I’ll save you the effort of having to scroll through 192 lines of Thread X is starting.

π = 3.141767987713553

Calculated in 48000000 iterations across 192 threads

Percentage error: 0.005581058497816649%

real 0m0.554s

user 0m6.459s

sys 0m0.015s

There’s still no significant change to execution time. That sys time is definitely still getting bigger as more threads spawn.

The future of pi_overkill

At this point, with version 0.2.2, I’ve essentially fulfilled my goals of learning Rust and practicing parallelization using it. However, that doesn’t mean I have to stop. There’s more I can add to pi_overkill to make it more… useful. Here are some minor additions I could make in the future:

- Letting the user choose the number of threads and iterations via command line arguments

- Offering verbosity levels, so you can see as much or as little of the process as possible

- One mode would spit out only the result, which is ostensibly useful for bash scripts that really need a programmatically estimated value for pi

A long-shot future addition would be to move this work to the GPU using OpenCL or something, but that’s something for future me to learn and then forget about.